EPA

EPA

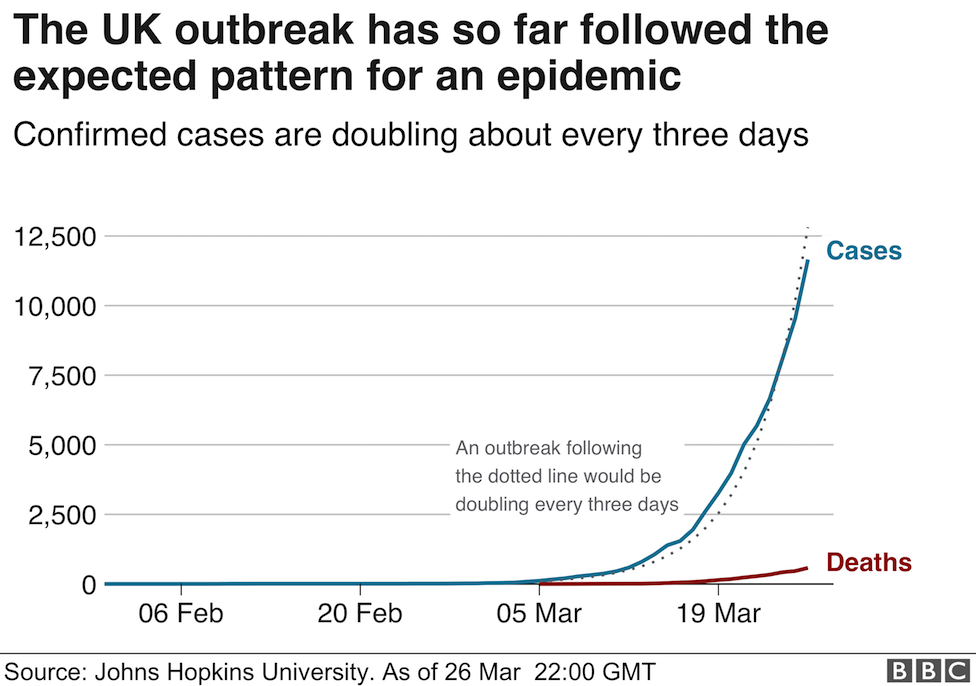

Deaths and confirmed cases of coronavirus in the UK have been doubling every three days, and on Friday the country experienced its biggest increase in deaths so far.

Models of the epidemic give very different estimates of its potential final death toll, from tens of thousands to one published on Friday that projected a figure of below 7,000.

So how to make sense of the projections, and what do the patterns of coronavirus deaths in other countries tell us about what could come next in the UK?

How do things look in the UK?

Confirmed cases in the UK are doubling every three or four days. Deaths are growing faster, doubling every two or three days.

This data doesn't show all cases, just the confirmed ones. That's because testing is mainly only carried out on those ill enough to be hospitalised, not those with mild symptoms, and so the true number of cases is higher.

Experts in the field would expect those wider cases to also follow a similar pattern: doubling every few days. That's because viruses multiply and so do the numbers of people infected by them. They keep multiplying at a constant rate until they run out of people to infect or measures to slow the spread take effect.

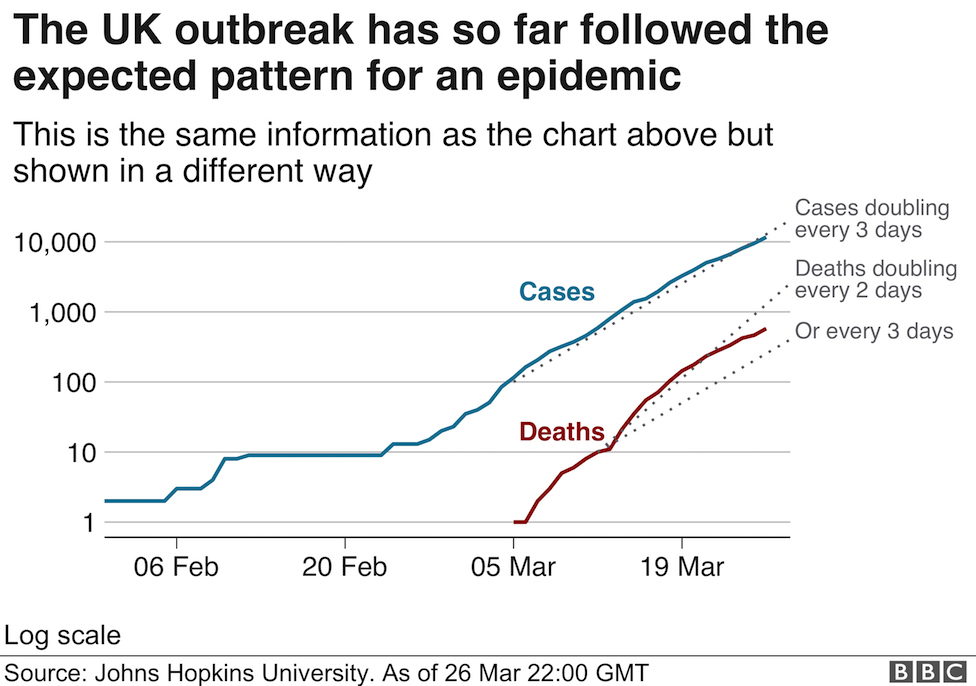

It's hard to see this constant multiplication from the chart above, but easier to see if you plot the same figures on a different scale.

On the scale shown below, a straight line means "doubling at a constant speed". We have added dotted guide lines on the chart to show what might be expected if cases or deaths were doubling every two or three days.

In reality, doubling speeds often fluctuate until an epidemic reaches a big enough number, say 100 cases. Since that point, confirmed cases in the UK have doubled every 3.3 days.

Thankfully, there haven't been enough deaths in the UK yet for us to draw a settled trend from 100, so our trend line starts from 10.

At the moment, deaths are growing faster than confirmed cases, doubling every 2.5 days.

As of 27 March, the UK has seen 759 deaths. If the speed of doubling continued, we would expect to see another 750 deaths in the following three days and 1,500 in the 2.5 days after that. But is that speed faster or slower in the UK than in other countries?

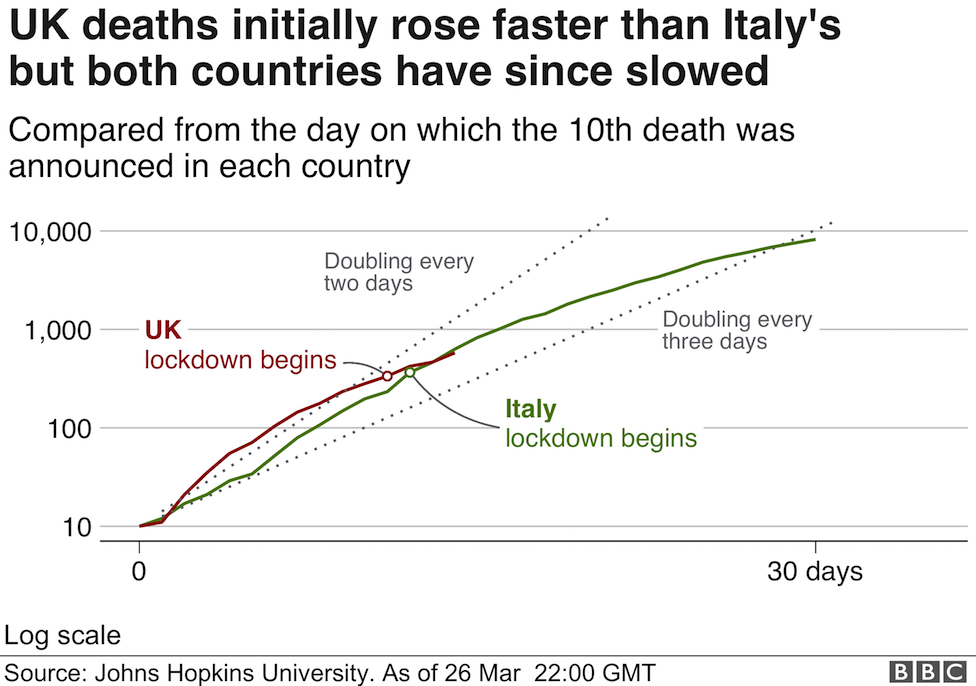

Is the UK on the same path as Italy?

Italy has the most advanced epidemic in Europe, with the most confirmed cases and the most deaths.

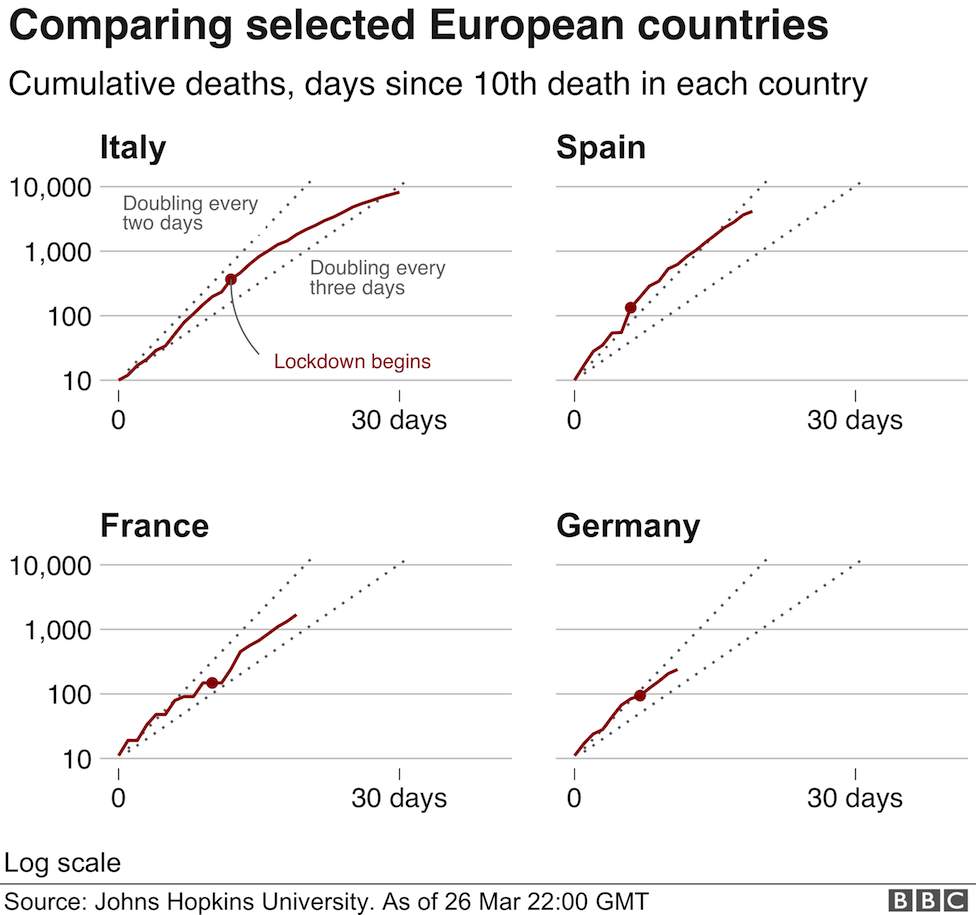

On average, the number of deaths in Italy has doubled every three days, but that masks rapid growth for the first 1,000 deaths followed by a slower pace of growth, suggesting that the course of the epidemic is changing.

In other European countries, the early numbers of deaths are also following that pattern of doubling every two to three days.

One notable exception is Spain, where the number of deaths does appear to be rising faster than elsewhere (every two-and-a-quarter days) well past their 1,000 death, although it is unclear why.

Does that mean the UK is only a few weeks behind a peak like Italy's? Not necessarily. Each country has a different healthcare system and is taking different measures to control the spread of the virus. The number of deaths depends both on the spread of the virus and the treatment that people can access when they have it.

The future in each country will depend on the actions governments and citizens take.

7,000 deaths?

Analysis by Rachel Schraer, health reporter

A paper released on Friday projected that fewer than 7,000 people would die of coronavirus in the UK in total. This figure is much lower than that in the modelling used by government.

So where did they get their numbers from? To get to these projections, Prof Tom Pike used the trajectory of death numbers in China to predict the progress of the UK and other countries' outbreaks.

But experts in viruses and epidemics have cautioned against assuming that countries will follow the same trajectory, even if there are similarities in early figures from each country.

There are some things that will be the same the world over like how long the virus takes to become infectious in someone's body. But how an outbreak develops after that depends on what measures countries take and when they act, and China brought in restrictions sooner than many other countries.

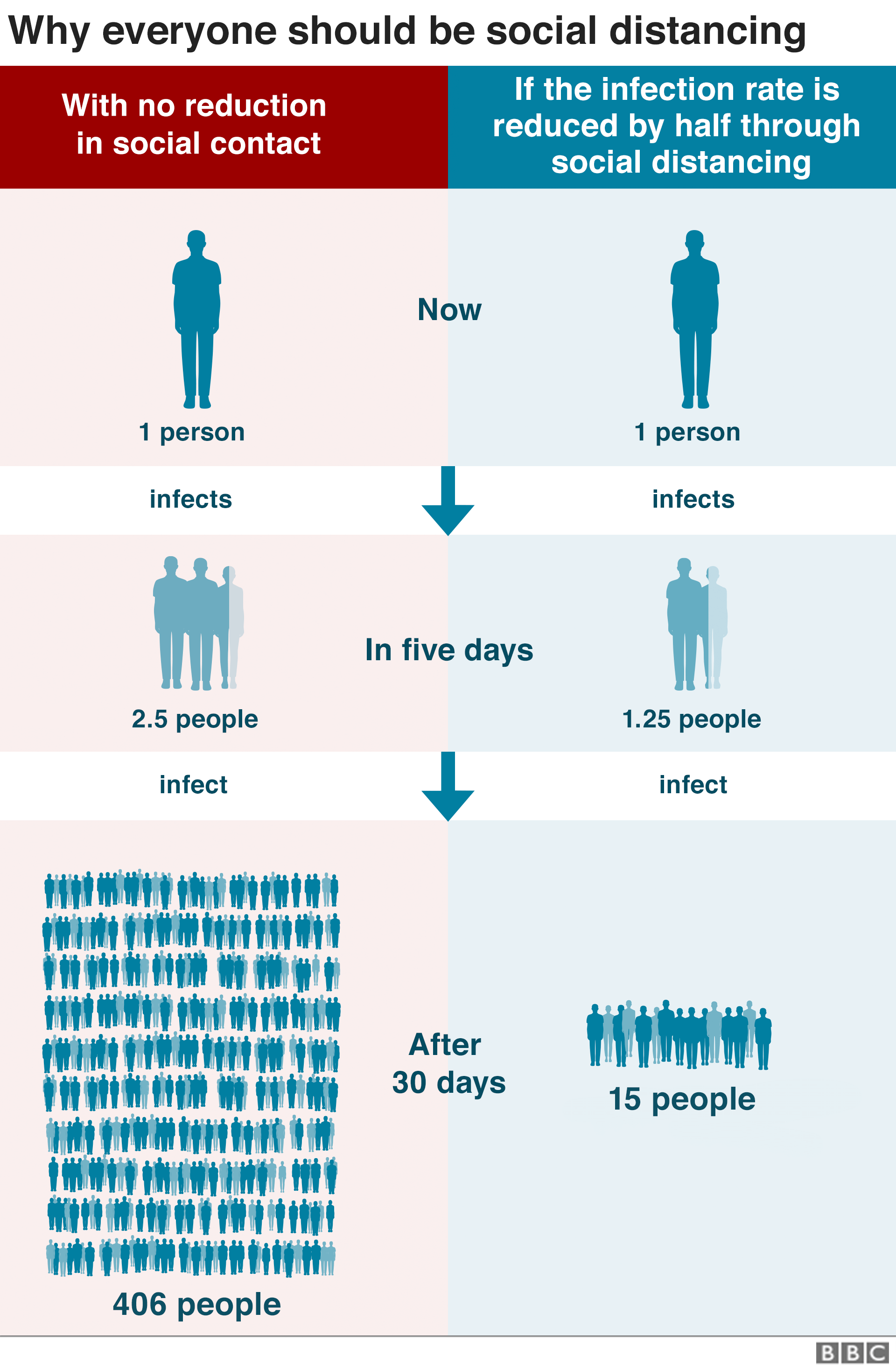

Small changes in the infection rate add up over time to big reductions in the number of new infections.

Scientists expect that each infected person will infect about 2.5 other people on average. As each of them infect another 2.5 and so on, a month multiplying at that pace leads to more than 400 new infections.

Halving that infection rate means that after a month, we'd expect to see just 15 new infections - a 95% reduction. That's because a small difference in the infection rate builds and builds to make a big difference in the number of people becoming infected.

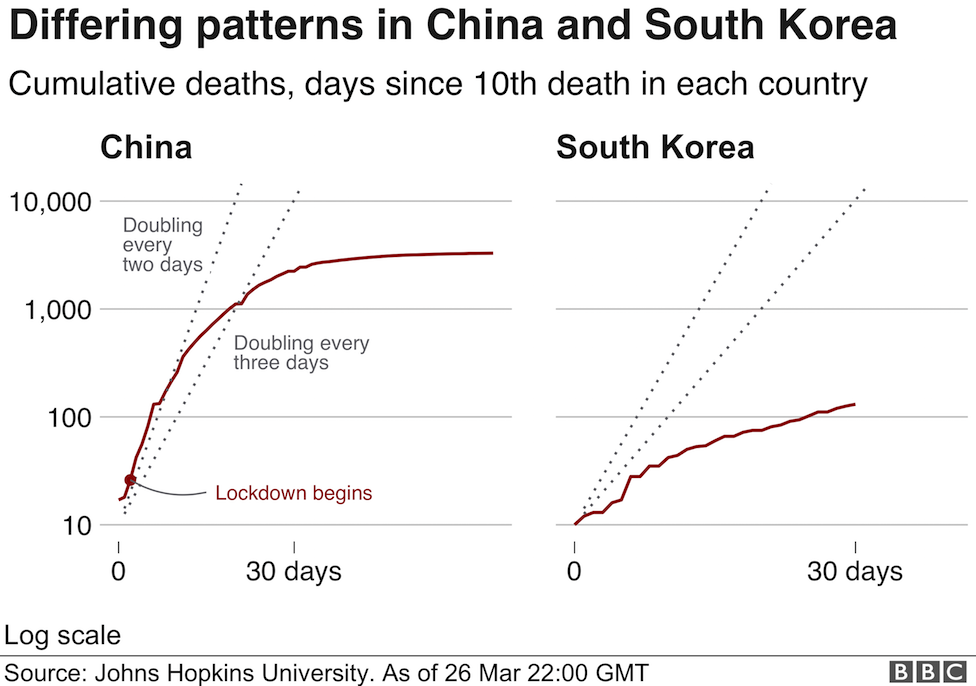

The path of the epidemic in China and South Korea show how it is possible to slow the spread.

China implemented severe lockdowns in Wuhan and Hubei province late in January before they saw 30 deaths. At that point, the epidemic was growing rapidly. About 10 days later, the number of deaths started to decelerate, slowing down to doubling every three days, and now growing far slower than that.

The total number of deaths has kept rising, but the number of new deaths each day has slowed and eventually shrunk.

South Korea and Japan never saw the same growth in deaths as other countries. They consistently grew at a slower rate, taking over a week to double.

South Korea rapidly began testing and tracing at scale, using almost 30 hospitals where suspected or confirmed cases could be isolated.

When will we see a change?

Prof Neil Ferguson of Imperial College, who developed the modelling used by the government, says it takes time before any measures, such as social distancing, have an effect.

People are infected, incubate the virus, develop symptoms, worsen and require hospital treatment before they get confirmed as carrying the virus. After that, it takes time before a case reaches the stage where intensive care is needed and then succeeds or someone dies.

The number of confirmed cases can give a hint earlier, since it takes less time to reach testing than the outcome of death.

It's only a hint, since changes in testing policy or capacity can change the number of confirmed cases.

But Prof Colin Baigent of the University of Oxford says the evidence is that lockdowns are working.

No comments:

Post a Comment