By Chris Baraniuk

Technology of Business reporter

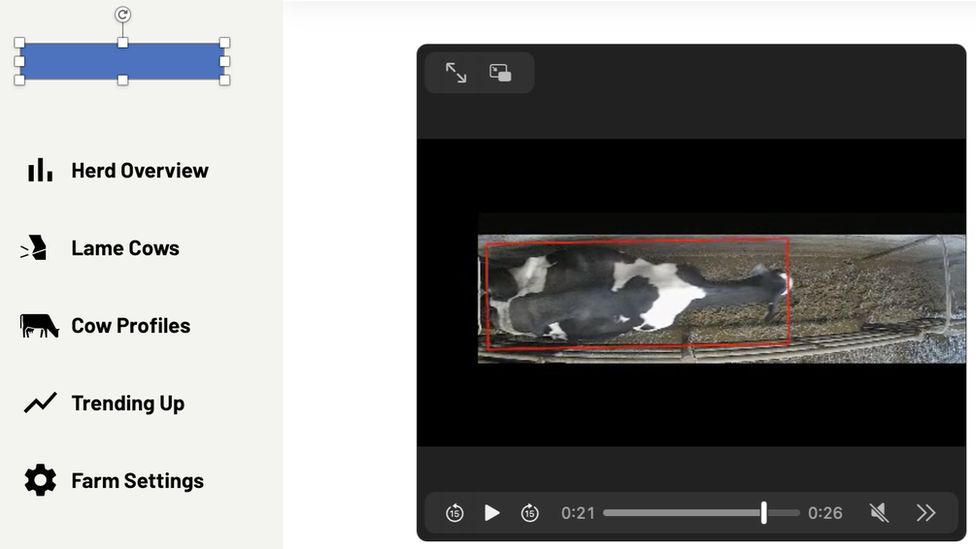

As cow number 2073 makes her way out of the milking shed and passes in front of a nearby camera, the computer identifies her and watches every step.

She is only on screen briefly but here is a slight unevenness to her gait, which she is trying to hide.

A human might not notice that something is wrong but the machine picks it up.

"Really, we want to completely replace any manual watching of animals when the cow sleeps, or she eats," says Terry Canning, co-founder and chief executive of CattleEye.

His firm's technology automatically detects early signs of lameness in cattle. It is confined to milking sheds, for now, but is already being rolled out on dairy farms, mostly in the US and UK. About 20,000 cows are currently under the system's watch.

Farms are increasingly turning to automation for many reasons - among them, to cover labour shortages. But new tech also offers potential improvements in animal welfare and a reduction in emissions, says Mr Canning.

"We've actually calculated, that if you can reduce lameness levels by 10% on a farm, there's a saving of half a tonne of carbon per cow per year," he explains.

Lameness is caused by injuries or infections and can be very painful. Lame cows produce less milk and if it goes untreated it can mean that they end up being culled.

University of Liverpool researchers have studied CattleEye's system on three farms to check its accuracy.

In research funded by the firm (which is yet to be peer-reviewed), Prof George Oikonomou and his team compared mobility scores for cattle made by two human experts with those made by CattleEye. They found that the technology was roughly 80-90% in agreement with the two experts - in terms of judging which animals were lame.

When 84 of the cows were subsequently checked for foot problems, the researchers found the AI system had performed slightly better than a human expert in terms of selecting those that had tissue damage in their hooves among the animals it had designated as lame.

A separate study, also led by Prof Oikonomou but funded by the Welsh government's Farming Connect scheme, found the introduction of CattleEye at one Welsh dairy farm with 300 cows, saw the proportion of animals with mobility issues fall from 25.4% to 13.5% after six months.

CattleEye is just one system bringing higher levels of automated surveillance to farms. Other devices for tracking their health include Moocall sensors.

These are strapped to a cow's tail and indicate when they are about to give birth. The sensors pick up a characteristic up and down motion of the cow's tail that occurs prior to calving.

Yet, there are plenty of farms that have not yet adopted these technologies. Dr Sarah Lloyd, her husband and family, run a farm in rural Wisconsin with about 400 cows. All of the milk they produce goes for cheese production.

"The cost of the technology just can't be borne by our milk price," she says. Her husband Nels Nelson prefers to work "with his sleeves rolled up" rather than rely on machines, she adds. He's not anti-tech but the family don't see a benefit in investing in AI-based systems.

Others take a different view. Dr Jeffrey Bewley is an analytics and innovation scientist at the dairy cattle breed organisation, Holstein Association USA. He grew up on a Kentucky dairy farm and has studied the industry "my entire life". He has done some consulting work for farm tech firms, though not for CattleEye.

He says there are tell-tale signs of lameness in cattle that farmers will spot - cow's back might arch a little bit, her head may bob or the length of her strides will get noticeably longer or shorter.

But lameness is something that cows naturally try to hide because they have evolved as prey animals. So, technology that helps the farmer spot the earliest subtle signs of lameness could be useful, he explains.

The animal charity RSPCA says it welcomes new technologies for monitoring cattle, as identifying lameness can be quite subjective for human observers and so such systems could make mobility scoring more accurate.

But the organisation says that since these are novel technologies and their validity is still developing "they cannot replace regular mobility scoring using a valid, reproducible method".

AI will gradually play a bigger role on our farms - but exactly to what extent is unclear, and whether it will really improve conditions for the animals themselves?

"I've been in several bulk barns, several dairies that are shifted to robotics and the cows are just friendlier. You can walk among them and they don't seem to be excited at all," says Jack Britt, professor emeritus at North Carolina State University, who has consulted for various farm tech companies.

Yet, not all interventions have to be high tech. Simply adding grooves to the concrete on which cows walk to and from the milking shed, can improve their stability and reduce their chance of becoming lame, he says.

Nonetheless, he predicts in 50 years' time 90% of the human labour on farms will be replaced by machines.

It is not a vision shared by Dr Lloyd. While she accepts it can be challenging to find human farm workers, she would rather keep trying than turn to machines. "I'd prefer to have more human eyes working on farms and making a living," she says.

"That's important for the economic life and social life of our community."