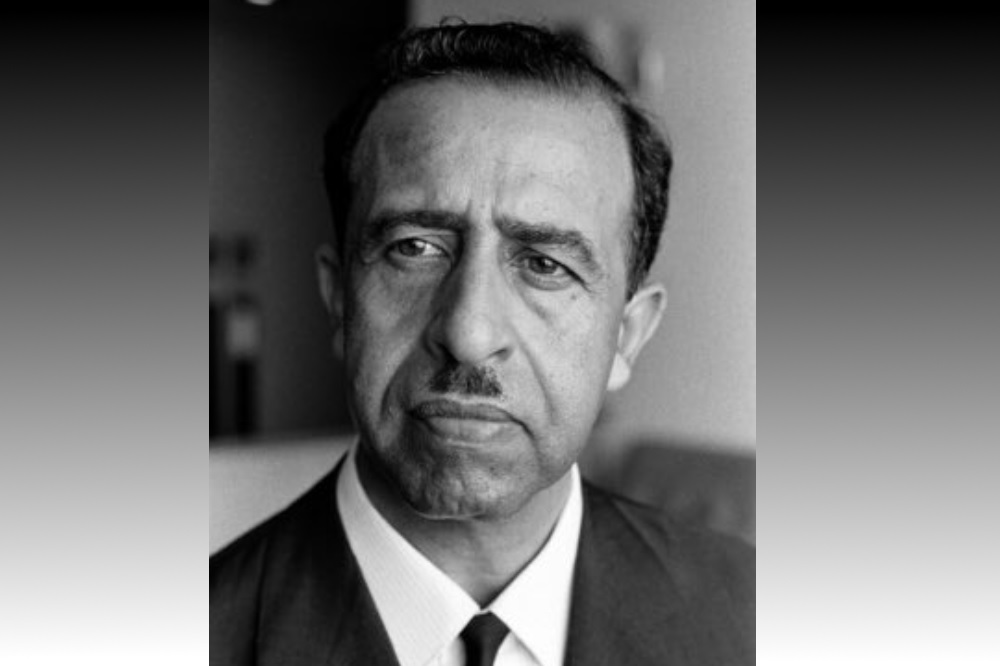

Ian Johnson

My hometown, Barry, is a remarkable place which has produced some remarkable people.

Former Plaid Cymru leader, Gwynfor Evans, was named the 4th most important Welsh person of the last Millennium.

The story of Gareth Jones, who wrote about Stalin’s man-made famine in the Ukraine, has recently been turned into a Holywood film.

But few in Wales could tell you much about Abdulrahim Abby Farah, the man from Barry who became a senior United Nations diplomat, leading the 1990 UN Mission that oversaw the dismantling of South Africa’s apartheid state.

Farah was born in October 1919, the year of the Race Riots; only weeks after the murder of Chilean sailor, Jose Martinez, on a neighbouring street to Thompson Street where Farah was raised. His mother, Hilda Anderson, ran a boarding house while his Somali father, Abby Farah, was a sailor and entrepreneur.

The young Farah attended Gladstone Primary School and Barry County Grammar School, while his parents were amongst a group which founded the multiracial Domino’s Club on Thompson Street. Most of the street was later erased in clearances of the Barry Docks area running south of Holton Road, a less famous and less romanticised version of Cardiff’s Tiger Bay. His father was a member of Thompson Street’s Colonial Club Committee and awarded an MBE for his wartime support for international sailors.

As a seventeen-year-old, Farah was sent to Hargeisa, in British Somaliland, where he became a clerk and then magistrate with the British Colonial Services, fighting in World War Two as a commando for British Forces in East Africa.

After the War, he graduated from Exeter and Oxford in civic administration, before returning to the horn of Africa, where he spent the 1950s working in the Trust Territory of Somaliland, the Italian administered territories which had Mogadishu as a capital.

The independent Somali Republic in 1960 was formed by the merger of the two British and Italian protectorates, the British Somaliland in the north understandably being the region with closest links to Wales.

In 1961, Farah became the Somali ambassador to Ethiopia, then under the rule of Emperor Haile Selassie. This was perhaps the biggest role for a Somali diplomat – as the two neighbours continued an ongoing border dispute over the Ogaden region, considered part of a ‘Greater Somalia’. He represented the new country at the Organisation of African Unity and to the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa.

In 1965, he became the permanent representative of Somalia to the United Nations, a post he held until 1972. During that era he served as Acting Director of Somalia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and, in 1969, became the Chair of the recently formed UN Special Committee on Apartheid, created by UN resolution 1761. Many Western countries did not participate in the committee’s early years because they would not support an economic boycott of South Africa.

Somalia underwent regime change from 1969 onwards. Mohamed Siad Barre’s revolution declared Somalia a socialist state, and it appears that Farah, who was linked with the previously elected Somali Youth League, took a backseat in terms of Somali domestic politics.

Barre led Somalia to a disastrous war with Ethiopia in 1977-78, and the 1980s civil war and attempted genocide brought about the 1991 Somaliland declaration of independence for the north, the former British colony. Since that time, Somaliland has self-governed, whilst the remainder of Somalia is frequently described as a failed state lacking in democracy and governance.

‘Moral order’

Internationally, Farah continued his work. He is credited with arranging the UN’s meeting in Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa, in 1972 – the first time since the permanent location in New York was established in 1952 that they had met elsewhere. He was President of a six-day UN Security Council meeting on ‘Questions relating to Africa’, alongside Umar Arteh Ghalib, with votes taken on resolutions about independence for Namibia, criticism of South Africa’s apartheid regime and ongoing repression in Portuguese territories in Africa.

Writing in 1974 on apartheid, he began his case by arguing that: “The existence of the Government of South Africa’s apartheid policy which is racism in its most extreme form — is a challenge of the same moral order as slavery in the eighteenth century, or the Nazi persecution of the Jews in the twentieth century.” This was a diplomat who wasn’t sat on the fence.

Back in New York, Farah continued to work within the United Nations, becoming first an Assistant Secretary-General for Special Political Questions between 1973 and 1978 before becoming the Undersecretary General from 1979 until 1990.

In 1990, Farah led the UN Mission on ‘Progress made on the Declaration on Apartheid and its Destructive Consequences on South Africa’, effectively the dismantling of South Africa’s apartheid state, meeting the newly freed Nelson Mandela, South African President F W de Klerk, and completing the work of several decades of campaigning at international non-governmental level.

In ‘retirement’, Farah helped to start the Partnership to Strengthen African Grassroots Organisations, Pasago, which he chaired, and established a hospital for landmine victims in Somalia.

Abdulrahim Abby Farah died in New York in May 2018, aged 98 years old.

In writing this brief biography, I make no claim to be an expert on Abdulrahim Abby Farah. If I have misunderstood or misinterpreted his aims, goals or beliefs, I apologise, and am happy to be corrected so that our understanding of him can be improved. But that is perhaps my point: how is a man who clearly achieved so much in the world, remain so unknown in the country in which he was born and raised?

I also offer no expertise in Somali politics, but hope that readers will recognise the importance of Cardiff-based organisations the Hayaat Womens Trust and the Somaliland Mental Health Organisation, and also reflect on how little most of us know about Somalia considering its centuries-long relationship with our communities in Wales.

No comments:

Post a Comment