- 9 hours ago

- Science & Environment

A complete camel skeleton dug up from a 17th-century Austrian cellar shows tell-tale signs that it was a valuable riding animal in the Ottoman army.

It was probably left behind or traded in the town of Tulln following the Ottoman siege of nearby Vienna in 1683.

DNA analysis shows that the beast - the first intact camel skeleton found in central Europe - was a Bactrian-dromedary hybrid, popular in the army.

It also has bone defects that suggest it wore a harness and was ridden.

The find is reported in the journal PLOS One and emerged from an archaeological dig that took place amid preparations for a new shopping centre in the town.

Bred for war

Researchers discovered the completely preserved skeleton amongst ancient household rubbish, flagons, plates and pans that had been dumped into a filled-in cellar.

First author Alfred Galik said it took a few guesses before he realised his team had stumbled upon something quite unusual.

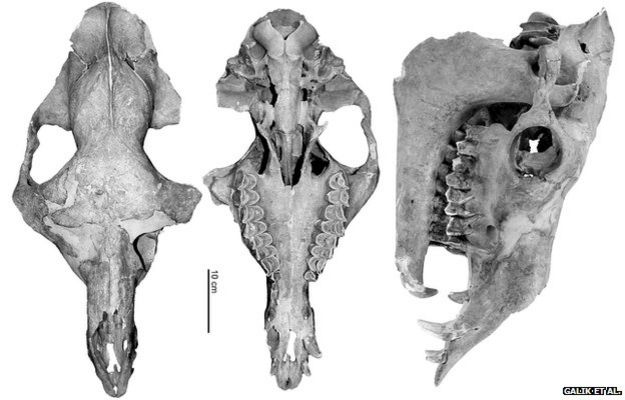

"First I saw the mandible, which looked a bit like a strange-shaped cattle; then I saw the cervical vertebrae, which looked like horse," Dr Galik told the BBC.

"Finally, the long bones and metapodials [foot bones] identified the skeleton as a camel."

Although other partial skeletons have been reported, including several dating from the Roman era, finding an entire camel was a first for central Europe.

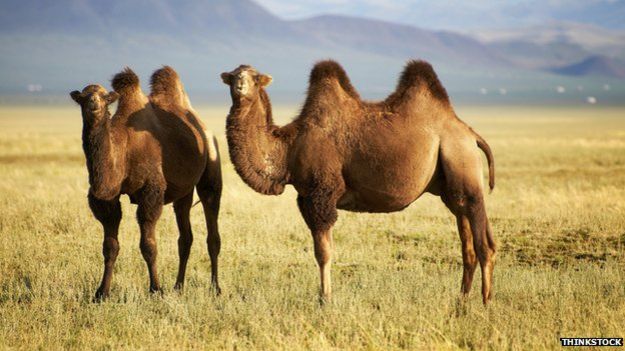

The shape of its skull - alongside subsequent genetic tests - confirmed the animal was born to a one-humped, dromedary mother and a two-humped, Bactrian father.

"Such crossbreeding was not unusual at the time," said Dr Galik. "Hybrids were easier to handle, more enduring, and larger than their parents. These animals were especially suited for military use."

The 1683 Battle of Vienna is perhaps better known for the massive, 20,000-strong cavalry charge led by the Austrians' Polish allies. But the invading Ottoman forces also used both horses and camels for transport and fighting purposes.

Career highlight

The Tulln skeleton shows symmetrical wear-and-tear consistent with being ridden, but not the evidence of strain expected for a beast of burden, Dr Galik said. This was a well cared-for, valuable animal.

It is also interesting because it was found inside the town, which was surrounded but never captured by the Ottomans.

The researchers suggest it may have been traded or left behind by the invaders, after they lost the battle for Vienna. The townsfolk may then have kept it as a curiosity.

Crucially, this would explain why it was not butchered and eaten, as the army probably would have done. This practice is probably responsible for the scarcity of intact specimens like this one.

The only other intact camel found across the Ottoman Empire's former European territories was a dromedary, recovered from sediments in the ancient harbour of Yenikapi in Istanbul - much closer to the animals' traditional heartland in the Middle East and Africa.

Dr Galik said the surprising discovery was a highlight in his scientific career, describing it as "an archaeozoological treasure".

Follow Jonathan on Twitter

No comments:

Post a Comment