- 2 hours ago

- Science & Environment

Nasa's Messenger mission to Mercury has reached its explosive conclusion, after 10 years in space and four in orbit.

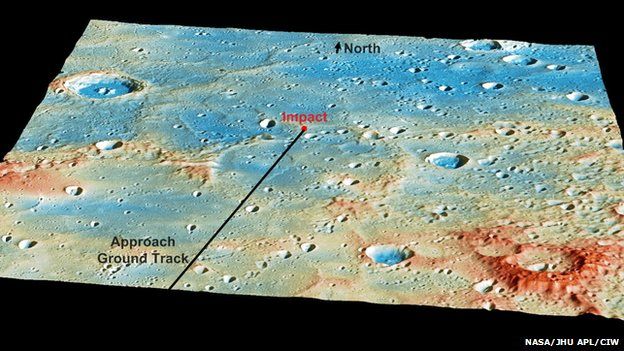

Now fully out of fuel, the spacecraft smashed into a region near Mercury's north pole, out of sight from Earth, at about 20:00 GMT on Thursday.

Mission scientists confirmed the impact minutes later, when the craft's next possible communication pass was silent.

Messenger reached Mercury in 2011 and far exceeded its primary mission plan of one year in orbit.

That mission ended with an inevitable collision: Messenger slammed into our Solar System's smallest planet at 8,750mph (14,000km/h) - 12 times quicker than the speed of sound.

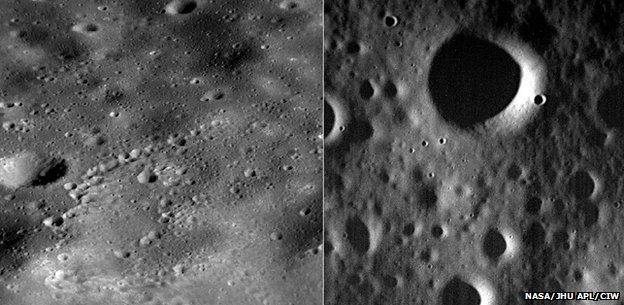

The impact will have completely obliterated this history-making craft. And it only happened because Mercury has no thick atmosphere to burn up incoming objects - the same reason its surface is so pock-marked by impact craters.

According to calculations, the 513kg, three-metre craft will have blasted a brand new crater the size of a tennis court. But that lasting monument is far too small to be visible from Earth.

Messenger's fuel supply, half its weight at launch, was completely spent weeks ago but four final manoeuvres were conducted, to extend the flight as long as possible. These were accomplished by venting the helium gas normally used to pressurise actual rocket fuel into the thrusters.

The last of those manoeuvres took place on 28 April.

During its twice-extended mission, Messenger (MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging) transformed our understanding of Mercury. It sent back more than 270,000 images and 10 terabytes of scientific measurements.

It found evidence for water ice hiding in the planet's shadowy polar craters, and discovered that Mercury's magnetic field is bizarrely off-centre, shifted along the planet's axis by 10% of its diameter.

Skimming the surface

For four years - and 4,104 circuits in total - Messenger traced a highly elliptical orbit around Mercury. It regularly drifted out to a distance of nearly twice the planet's diameter, before swinging to within 60 miles (96km) at closest approach.

To maintain this pattern in the face of interference from the Sun, it needed a blast of engine power every few months, which meant the mission faced an inevitable, violent end when the fuel ran out.

No comments:

Post a Comment