- 6 hours ago

- India

Atish Patel

Atish Patel

Demand for good quality end-of-life care has grown globally as more people live longer with chronic conditions.

In recent years, countries like Mongolia and Uganda have been praised for making great strides in improving palliative care, which focuses on managing pain and discomfort caused by serious illnesses like cancer, HIV and strokes.

In India, however, the situation is dismal. Most Indians who need palliative care simply don't get it and die in excruciating pain.

Home to 1.3 billion people, India ranked 67 out of 80 countries in a study released last year comparing end-of-life care. The report considered the United Kingdom as the best place in the world to die.

Extensive programme

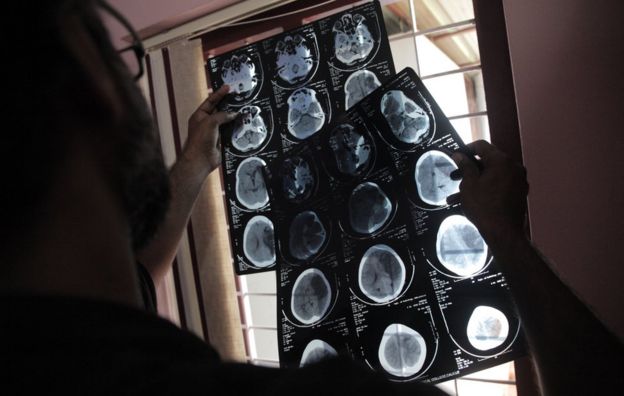

India faces major shortages in specialists, awareness and facilities.

But the southern state of Kerala is an exception.

It has more palliative care centres than the rest of the country put together and its extensive programme is bolstered by thousands of volunteers who give up their time to tend to those who are incurably ill, bedridden or nearing the end of their lives.

Atish Patel

Atish Patel Atish Patel

Atish Patel

Every week, people like Radha Upasarna assist specially trained physicians and nurses treating patients at home. They check for bedsores, deliver food, and often just listen and chat.

Mrs Upasarna says what she does is not only a service to her community, but a way to overcome bouts of loneliness she has experienced after her husband's death in 2014.

"It doesn't feel like work," she said. "It's just something I want to do."

Atish Patel

Atish Patel Atish Patel

Atish Patel Atish Patel

Atish Patel

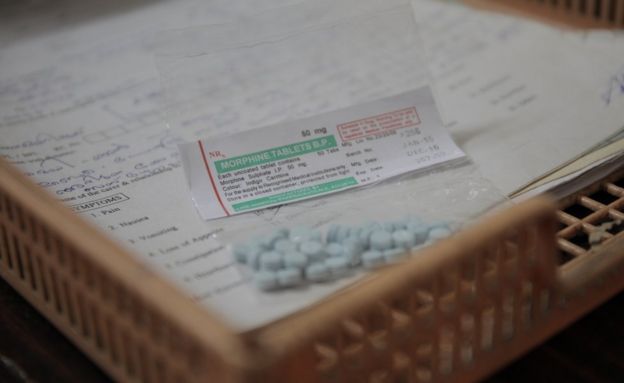

Care-givers say also what makes a huge difference is that morphine is available in Kerala's hospitals and at homes for patients who need it.

Despite being the gold standard to treat severe pain, access to the opium-based drug has been highly restricted in India over fears of addiction and misuse.

That means although India is the leading global producer of legal opium, almost all of it is exported to the West.

In 2014, in what was seen as a major step forward, the parliament amended national law to simplify procedures for doctors to prescribe morphine, but it has so far had little impact on the ground, experts say.

In Kerala, access is vastly better because the state changed its narcotic regulations almost 20 years ago.

Zubair, 55, had a series of amputations to his right leg as treatment for a bone tumour. Due to the agonising pain he continues to suffer even after being cured, he has been taking morphine since 1994.

'Destroyed lives'

MR Rajagopal, the doctor who first prescribed the painkiller to him, says he's an example of what morphine can do to a person even when a disease is not terminal.

Dr Rajagopal estimates that 99% of Indians who need morphine don't get it and "their lives are destroyed and they [often] take their own lives".

But for Zubair, who lives in the city of Kozhikode (formerly Calicut), "morphine restored me back to life".

Although other states in India have largely failed to provide access to effective painkillers and palliative care, particularly in rural swathes, initiatives are slowly emerging outside of Kerala.

Nadia district in the eastern state of West Bengal, for example, started a home-care programme in 2014 to assist hundreds of needy villagers.

Atish Patel

Atish Patel

Called Sanjeevani (which means life giving in Sanskrit), the programme has benefitted patients like Dayal Durlav, who is battling oral cancer.

The 62-year-old's family refuses to look after him, believing that his illness is contagious because the same type of cancer claimed his brother's life. Dispelling such myths is a part of what the programme's volunteers, nurses and doctors have been trained to do.

"I'm grateful they come to see me," Mr Dayal said. "I'm old and I need their help."

This report was supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. Follow Atish on Twitter @atishpatel

No comments:

Post a Comment