- 13 March 2015

- Business

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES

Since the dawn of the industrial age, the world has been steadily getting wealthier, despite setbacks such as the Great Depression and the more recent global financial crisis.

We make more, sell more and consume more than ever before.

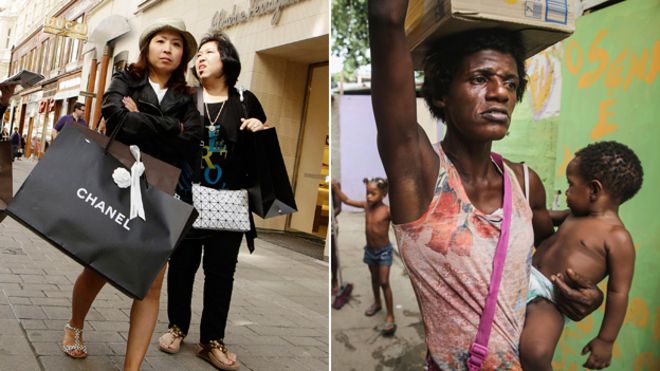

Yet, according to the United Nations, nearly three billion people still live on less than $2.50 (£1.70) per day.

So, how can we raise living standards for those who still live in poverty? The answer, according to most governments, is rapid economic growth.

Growth is seen as a panacea for a great many ills. It creates jobs, erodes debts and raises living standards. For politicians, it also generates votes. It is almost universally seen as a Good Thing.

Journalists are complicit in this. We frequently describe rapid growth as "robust". Slower growth is "anaemic" and an economy in recession is often portrayed as "sick" or "ailing".

'Boiling the oceans'

Yet there's a problem here. We live on a finite planet, but growth is exponential. So an annual increase in gross domestic product (GDP) of 3% might not sound like much - but it means an economy will double in size every 23 years.

THINKSTOCK

THINKSTOCK

So does this matter? According to Tom Murphy, professor of physics at the University of California San Diego, it definitely does, as economic growth goes hand in hand with increasing energy consumption.

"From a physical point of view, if we grew at 3% a year, in about 400 years' time we would actually be boiling the oceans - not because of global warming and CO2, but just because of the heat that is a natural by-product of the energy that we use," he says.

These physical constraints, Prof Murphy says, will start to have an impact - for example, by creating cycles of boom and bust - and will make long-term growth impossible.

Accessible energy

This view is not entirely new. In fact, the English cleric and scholar Thomas Malthus made a similar point back in the 18th Century. His concern was not energy use but population growth.

He believed that the population would grow as living standards rose, and that eventually food supplies would run out. That hasn't happened so far. In fact, we have simply become much better at producing food.

So could we do something similar with energy?

THINKSTOCK

THINKSTOCK

"There's potential to get renewable sources of power that don't produce carbon emissions, that are cheap and easily accessible," says economist and environmental campaigner Yoram Bauman. "The goal is to get the cost of renewable power below the cost of, say, coal."

Certainly there's little sign of anxiety within the financial industry.

"Historically, people have demonstrated a remarkable ability to deliver economic development and growth, often in the face of appalling manmade and environmental catastrophes," says Joe Seifert, a former investment banker and now the chief investment officer for Indian fund Essar Capital.

"Resource scarcity in areas such as energy and water is a possible constraint, but there are vast natural resources that are untapped and human ingenuity has in the past overcome many such constraints."

The right growth

On the face of it, that should be good news for many developing countries, who rely on growth to create jobs and boost living standards.

But growth alone is not good enough, says Ashish Thakkar, founder and chief executive of the Africa-based Mara Group. It needs to be the right kind of growth.

"Growth should not be about speculation and making a quick buck," he says. "It's seen as helping to lift people out of poverty, but we mustn't lose that mindset. It should not be about simply creaming away natural resources."

THINKSTOCK

THINKSTOCK

He thinks growth can still have huge benefits for developing countries.

But the well-known - and frequently controversial - Indian environmental activist Vandana Shiva has a very different view.

She believes that current measures of growth place too much emphasis on potentially harmful activities, such as logging or mining, and do not value natural wealth.

"Every story of growth is a story of environmental footprint that was encountered, of social dislocation," she says. "Growth is only measured in terms of commodification. It doesn't measure the life you're living, the nutrition you're eating, the quality of your life."

'Work for hands and heart'

She thinks we need to redefine what we mean by wealth and accept that economic growth often comes with a hefty price tag.

"Being rich means living a full life, living a life of meaning," she says. "Having work for your hands and your mind and your heart. Having a wide circle of compassion to give. On that there is no limit."

One person who might have some sympathy for that view is Gillian Tett, the US managing editor of the Financial Times. But she is also a graduate in social anthropology, the study of peoples and how they relate to one another.

She believes the vision of growth put forward by orthodox economists is too narrow.

"People don't think about their lives in terms of numbers in a bank or in terms of numbers and spreadsheets. They look at their total sense of wellbeing and prosperity. Maybe that's the kind of thing we should be focusing on much more these days," she says.

So perhaps, if we want to get richer forever, we should go back to the drawing board, and start to rethink what being rich actually means.

For more, listen to Can the world get richer forever? on BBC World Service at 20:05 GMT on Sunday, 15 March.

No comments:

Post a Comment